Some of you may be familiar with Winner’s article Do Artifacts Have Politics? in which Winner discusses how nothing is free of the inherent grip of

political motivation. From television to highways to mechanical plant

harvesters, everything we see day-to-day has some (purposeful or not) political

consequence. This phenomenon is not just limited to technological creations,

one of the most powerful political motivators, and also one of the most

reflective artifacts of the society in which it exists, is art.

“Does are reflect culture, or shape it?” is a question which

has been asked by artists and philosophers for a very long time. Whether one or

the other is true there is an undeniable link between society and art, and even

more so between art and politics.

Politics have been inherent in art since the beginning of recorded

history. In Ancient Egyptian culture the

people ruled not by the power of a king, but by belief that their king was

actually directly related to the gods. In Ancient Egyptian art figures were not realistically represented,

instead they were symbolic. The Pharaoh, when depicted, was shown at a much

larger scale than those around him as a representation of his power. Those of

higher social tiers were generally larger, all the way down to slaves being represented

as being barely as tall as the Pharaoh’s knee. Only in such a society could a

construction such as the Sphinx come into being. A massive sculpture/structure depicting the head of a

Pharaoh on the body of a lion, think about the kind of message that sends about

the society that built it, and worshiped the man who had it built.

|

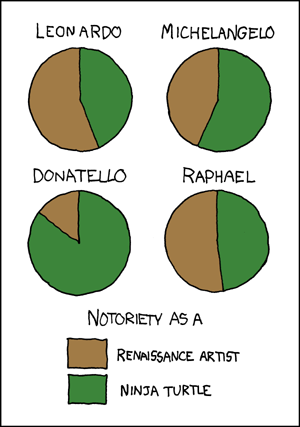

| Source: http://xkcd.com/197/ |

During the era of Ancient Greece art took a different turn.

From the City States that created the prototype for the ideal political system,

came also the ideal of perfect figurative art. Ancient Greece can be considered

the starting point for the pinnacle of high classical artwork. They defined the

cannon of proportions, the layout of the human anatomy, and much more that went

into creating the ideology of realism. Greek art was obsessed with the

individual, the character. Look at how reminiscent this is of the Greek democracy; where the people

make the rules; where the individual creates

the society. There is more to it than

that, as Plato laid out in his political dialogues the society is the entity, and the individual is a piece of that creation.

The important thing though is that the Republic stands on the supporting

pillars that are the people, and it is this focus on the personal character that

we see reflected in their art.

In stark contrast to classical Greek realism there lies medieval

art. During this era the western world was dominated by the Papacy. As such the

focus of civilization was considerably shifted, instead of the focus the

individual character or even on society the focus was on religion. Art

throughout this era attempts to convey not the solidity of reality, but an

otherworldly ethereal realm. Similar to Ancient Egyptian art, character central to religion are represented

as larger characters, important objects and concepts are focused on and lesser

items are merely a backdrop.

This leads us to where we are today: modern society and

modern art. This is a topic which has no definitive resolution, and is still discussed.

Art has become something which is no longer defined. It is no longer measurable

or quantifiable. Modern art seems to have become a personal “experience”, dependent upon the meaning that a given individual gives to an “art piece”.

Without any empirical measure of what art means today, there is no longer any

definition of “good” and “bad”, merely “art”. This personal relativity of art

(so to speak), has created a unique definition. Whereas art in previous

societies has a purpose or a meaning, it now just is. “Art of art’s sake” is a saying that began in the 19th century, where some

of the roots of this abstraction may be traced back to. If modern art is

objective to the viewer, and there no longer exists a true quantitative measure

of the meaning of the art, what does this say about our culture? If art and

society are truly inextricable, when art no longer has an intrinsic identifiable

meaning and is not beholden to the values of “good” and “bad”, what has our

society become?

No comments:

Post a Comment